What is a Brain Arteriovenous Malformation?

A brain arteriovenous malformation (AVM), also called a cerebral arteriovenous malformation or simply AVM, is an abnormal tangle of blood vessels in the brain. AVMs can cause bleeding in the brain, seizures, and other neurologic problems. They occur in less than 1% of the population. Most patients are born with their AVMs but in some cases AVMs can form later in life. The most common age for brain AVMs to be diagnosed is in the 30’s to 40’s, but they can be diagnosed in children as well as older adults. Men and women are equally likely to have an AVM.

How are AVMs discovered?

Unruptured AVMs often cause no symptoms and hence are discovered “accidentally” after brain imaging for other reasons. The most common first symptom caused by an AVM is bleeding in the brain. This occurs in 70% of symptomatic patients. Patients whose AVMs bleed often have sudden onset of a severe headache, and may also have weakness, nausea, vomiting, neck stiffness or sound/light sensitivity. In severe cases patients may progress to coma. Bleeding is associated with a 10-20% chance of death and a 10-20% chance of disability. Less commonly, the first symptom of an AVM is a seizure(25% of symptomatic cases). The average age of patients with seizure is 25 years. Less commonly, the first symptom of an AVM may be weakness or other focal neurologic symptoms that leads to the identification of their AVM. Headaches are common in patients with AVMs, with 5-15% of patients complaining of long-standing headaches before their AVM is detected. However, most people with chronic headaches do not have an AVM. The best available data suggests that AVMs have a 1-3% per year risk of bleeding once discovered.

How are Arteriovenous Malformations Diagnosed?

AVMs are diagnosed in different ways. Diagnosis of an AVM that has caused bleeding is typically made on Computerized Tomography (CT), which uses X-rays to view internal structures of your body, in this case, of your brain. In patients where the AVM has not caused bleeding, often Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is also performed, which uses magnetic and radio waves to create high resolution images of the brain tissue and surrounding structures.

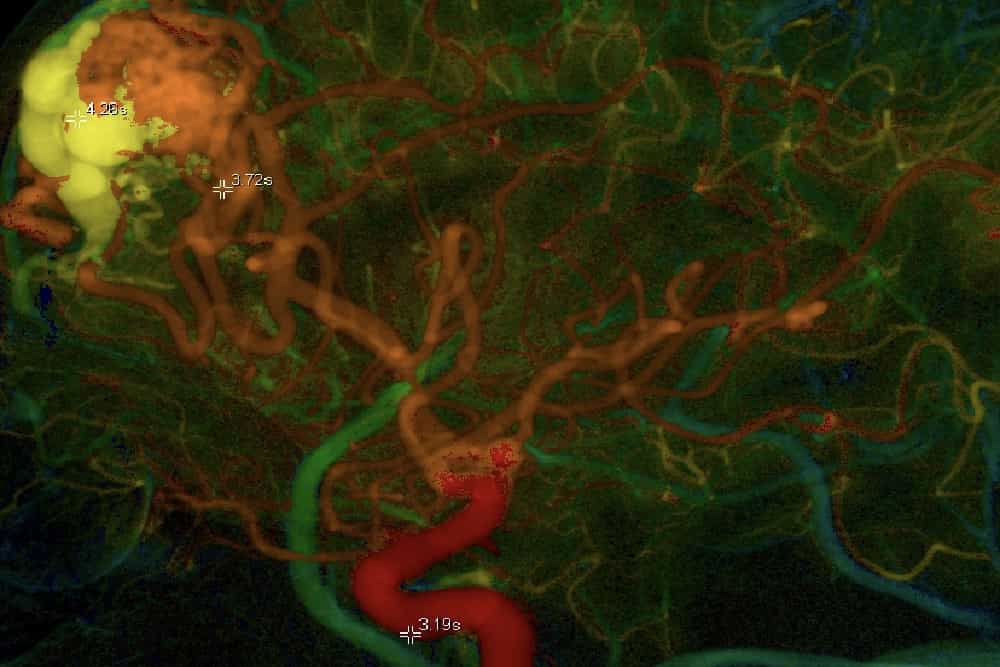

To determine the exact location, size and anatomy of an AVM, the blood vessels in the brain are imaged in a test called “angiography.” Angiography can be performed non-invasively with CTA or MRA. Cerebral catheter angiography is the third option, which is an invasive test that requires a catheter to be placed into the arteries that supply the brain in order to inject contrast material (“x-ray dye”) for imaging of the blood vessels. Usually the catheter is placed into the leg artery in the groin and maneuvered into the brain arteries. The procedure involves minimal discomfort and may be performed with light sedation (the patient is awake) or general anaesthesia (the patient is asleep). Angiography is considered the “gold-standard” for imaging an AVM. It is an invasive test, with a very small risk of serious harm to the patient (most importantly a small risk of causing a stroke). It is performed in conjunction with CT or MRI as it provides additional information.

How are AVMs Treated?

Today there are four management options for people who have been diagnosed with a brain AVM.

Medical therapy:

Medications are prescribed to manage symptoms if necessary (seizures for example). No effort is made to remove the AVM. This option may be chosen when attempts to treat the AVM with other means may pose more risk of harm to the patient than the AVM itself.

Surgical therapy:

This requires opening the skull (craniotomy) in order to remove the AVM. In order for surgery to have any benefit, the entire AVM must be removed. Surgery immediately eliminates the risk of bleeding from the AVM but can also cause harm to the patient depending on the size of the AVM and where the AVM is located. For example, removing a larger AVM in a part of the brain that performs important functions is riskier than removing a smaller AVM in a part of the brain than is “less important.” After removing the AVM, the skull bone is secured in its original position.

Radiosurgery:

Whereby a single treatment of highly focused radiation dose is used to obliterate the AVM. Radiosurgery is performed by a team consisting of a neurosurgeon and radiation oncologist. Unlike traditional surgery, the effect of radiosurgery is not immediate; once administered the radiation destroys the AVM usually over a couple of years. While not always effective, radiosurgery has high cure rates for smaller AVMs, and is often the treatment of choice for AVMs in locations where traditional surgery would be very risky. There is a small risk of bleeding in the brain (usually delayed), and there is a very small chance of delayed development of malignant tumors.

Endovascular therapy:

Tis is a minimally invasive procedure where catheters placed into the arteries, usually through the leg artery in the groin, are used to seal off the AVM with a glue-like substance (“embolization”). In some cases endovascular therapy alone can “cure” the AVM, but most AVMs cannot be cured this way. Most often endovascular therapy is used prior to radiosurgery or surgical removal of the AVM to make those treatments safer or more effective. The main risk of endovascular therapy is causing a stroke or bleeding in the brain.

Often multiple treatment options are combined, especially for difficult, large and complex AVMs. Selecting the appropriate treatment is critically important to give each patient the best possible prognosis. Patients are urged to seek treatment at centers that are experienced with AVM treatment and can provide all of the above treatment options.